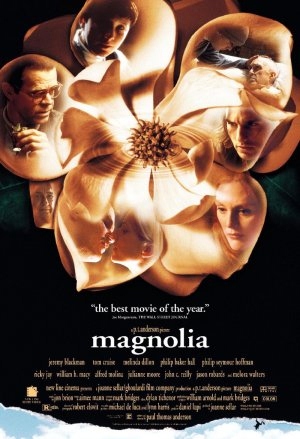

I was watching Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia last week with my brother, an acknowledged film nerd, and it reignited an ongoing conversation of ours. The film, if you haven’t seen it, and I recommend that you do, follows the lives of a good dozen characters, as their lives interweave and collide in Los Angeles. Near the end of the film, at the point each character reaches a moment of crisis, a torrential rain of frogs suddenly comes crashing down on L.A.

In my brother’s words, “You’re either a rain of frogs guy or you aren’t.” The scene has become famous more for its sheer strangeness than anything else; there are stories of people getting up and leaving the theater at that point. It’s not the only odd moment in Magnolia. Apart from the amphibious deluge, the film is over three hours long, and it also includes a montage in its middle where Julianne Moore, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Tom Cruise, William H. Macy and the rest of the cast are shown singing along to the film’s soundtrack.

The point being, the movie is strange. It also works perfectly. The rain of frogs and the sing-along montage are powerfully effective within their context. They may not make logical sense, but that’s not terribly relevant, I think. The point of films is not to tell a story; the point is to give viewers a particular experience using the mechanisms of narrative, and in the moment that they happen, those scenes do exactly what they were intended to. To take out the sing-along scene because there’s no logical reason that all the characters across the city would be singing it at the same time is to miss the point entirely, and would be to greatly harm the beauty and impact of the work as a whole. The rain of frogs scene is really weird, but it’s supposed to be weird. Its weirdness has the strange effect of making the world of the film seem more real.

Nevertheless, many people can’t sit through the whole movie. The same goes for other masterpieces like Tree of Life, perhaps the most transcendent piece of film I’ve ever seen. People walk out because they get bored, something I just cannot wrap my mind around. It’s frustrating for people like my brother, who spends more time than I do watching and reviewing movies, that people are always calling out for more originality in movies. They say they’re tired of the explosions, the formulas, the sequels. But when they get it, they get bored and walk out. Suddenly it’s “self-indulgent” or pompous. This same tendency is true in the world of videogames.

The problem is that all art is an imposition. Art confronts its audience with a personal vision, something the audience might not have wanted or expected, but which the creator believes that the audience ought to see. This experience might be painful, or uncomfortable, or possibly even joyful as something inexpressible is finally expressed, but whatever it is, it’s never something the audience wanted going in. If they knew exactly what experience they wanted, then the art would not affect them. Great art is unexpected and revelatory. It reaches outside of itself and alters the viewer’s universe.

Ultimately, this is why the claim that videogames will have “made it” when they have better rules, better graphics, or better dialogue is wrongheaded. Those things are the elements used to build an experience, they aren’t the experience itself. A piece of great videogame art would give its players something that they haven’t demanded, and in fact could never demand at all, because for it to be effective it would have to show them something new.

Further, great art earns its name by doing in its medium what hasn’t been done in others. Since the hallmark of games is their interactivity, the player’s actions should be the medium through which something unexpected is expressed. Common examples of games as great art include BioShock and the more recent Spec Ops: The Line. While I don’t disagree that these games are a cut above the rest (the things that you do as a player are what matters), they still fall short due to their inward-looking focus. Like the movie Funny Games, or, to a lesser extend Cabin in the Woods, they do offer a kind of revelation. However, it’s ultimately a revelation about the work itself and its genre, rather than anything that transcends itself.

But as difficult as it is to make the meaning of the game rest in its players’ actions, the greatest hurdle is the problem of authorship in games. Movies, music, paintings, literature and so on are single, unified experiences. They are carefully defined, circumscribed, finished. Games are not. Games are a massive array of possible experiences, some profound, some banal, some frankly irritating. Their rules are fixed but their events are not. They’re a uniquely malleable art form in which the player is a kind of co-author. The creator of a game can never be certain what experience the player will have, since the player is making up a great deal of that experience as he goes along. How can a game creator make every one of an infinite number of possible plays a profound, transformative experience? How can the player be startled and moved by the core of the game, when the core of the game is the player’s own activity?

It’s a problem that bothers me, and one I don’t have a good answer to. Perhaps we are asking games to be something they weren’t meant to be. They are practical creatures, more mechanisms of self-expression on the part of the player than an end in themselves. Would it be so wrong to consider them tools for making works of art, rather than works of art in themselves? Most of us have had a particular gaming experience that has resonated powerfully with us. However, upon going back later and trying to recapture that feeling we find it elusive, since it was born out of a particular set of circumstances that will never be repeated. Particularly in the case of multiplayer games, play seems to generate spontaneous dramatic stories that affect our lives outside the games, because they affect our relationships. Whereas works like Magnolia or Tree of Life present us with a finished vision we could never have anticipated, masterful games allow us to experience the strange and startling consequences of our actions, and perhaps it is those works, those unrepeatable, finite, chains of interactions we’ve built, that we ought to be celebrating, rather than the rules that build them.

“Movies, music, paintings, literature and so on are single, unified experiences. They are carefully defined, circumscribed, finished. Games are not. Games are a massive array of possible experiences, some profound, some banal, some frankly irritating.” Nonsense! You literally just wrote about how many people don’t bother to complete Magnolia!

Which part is nonsense? I don’t think I’m following your objection.

Ben, this is a really interesting article — The intersection between video games, rules and art is one that I’m really interested in. Approaching it from the side of being a visual artist who is also a gamer, I’ve found that confusion about games and art is hardly new. For instance, I just finished an amazing book called “Marcel Duchamp: The Art Of Chess” which looks at the intersection between Duchamp’s artistic production and his lifelong obsession with chess. The really crucial element that they bring up is that the kind of art produced in relation to games tends to be of a specific variety, which relies on what you might term mental mechanisms — that is, in chess, the pieces themselves are not the game. Instead, the rule set inside your head is the game. For instance, great chess players can play without the board quite easily and there is a whole set of notation that can give you the aesthetics and moves of a game without any board or pieces. The hypothesis is that this love of chess as a mental mechanism is partially responsible for why he was one of the early developers of what we now call “conceptual art.” In the same way, much game criticism seems to be focused on the tangible/visual elements of the game or the emotional responses. Instead of these two more “aesthetic” and “expressionistic” modes of thinking about art (and games) — this notion that Duchamp developed becomes a third stream of a way to experience and critique art: by looking at the way the mental system interacts with itself your mind. The work of Duchamp is directly what you’re speaking about with the “massive array of possible experiences.” (John Cage as well was very interested in game systems as well as generative methods for his works of art. After all, what could be more Dungeons & Dragons than rolling dice to determine the way a song goes!) My point isn’t to belittle the contemporary dialog, but instead to show that the interface of games and art has been quite long and quite bumpy.

Thanks, Eron, that was fascinating. I’m gonna have to read up about Marcel Duchamp, as those issues are exactly the kind of thing I’m interested in. I’ve gotten into arguments with friends over whether rules are art, and ended up defending them on the basis that the system of rules that comprise them can be a thing of beauty in itself. I’m not so sure now. While I definitely know of some rule sets I would describe as beautiful, such as Go, I haven’t encountered a rule set that has ever struck me as great art in itself, perhaps due to their practical nature. I’ve begun looking at game design more as a craft than an art, in that it’s ordered to an end other then itself. And it seems to me that things made for their own sake rather than for a practical end tend to be the most good/true/beautiful. As I mentioned above, it does seem that there is room for great art in games though, if you consider an actual instance of play rather than the rules. I’ve been struck how great chess or Go players, when commenting on a master-level game, will say that a particular move was profound, in much the same way that a critic would look at a great work of art. It’s those individual, incarnated instances that people admire. I’m coming to believe that game design is the design of art forms, rather than art works.