This article is part of our special series on Mental Health and Gaming, and was supported by community funding. If you want to help support future feature articles and special series, please consider donating to our Patreon.

“The mind of the subject will desperately struggle to create memories where none exist…” —Bioshock Infinite

“If we cannot find an explanation for what we are feeling, we will surely manufacture one…” —Peter Levine, In an Unspoken Voice: How the Body Releases Trauma and Restores Goodness. 183.

Something I never expected about living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is what it did to my sense of time. I can remember what happened in ugly, vivid detail, but I can’t always remember when. Did that happen before the hospital? Was this after the thing with the cops? Sometimes I’ll say it was five years ago and then realize it couldn’t be; sometimes I’ll say it was last year until a friend gently reminds me it wasn’t; sometimes it feels like it’s still happening, if a person or a place brings it back. I still have blunt, detailed nightmares where they tell me it was my fault, that I deserved it; this occurs without fail if I’m doing anything that could be remotely considered ‘healing’. These dreams pull my efforts back into the ceaseless current of that winter, whenever it was. The past rushes forward to engulf the present, taking the future with it.

It took a long time and a lot of work to name it as trauma, and even more work, still ongoing, to understand how I could keep it from destroying my life. Once the dust from that winter settled, I did my best not to talk about it unless I had to. I did my best not to deal with it, to pretend I’d gotten on with things, until I remember going downstairs for a cigarette two or three or four years later and suddenly realizing I couldn’t cite the last time I’d had an actual emotion. When trauma couldn’t destroy me I apparently decided to finish the job myself, killing every feeling inside me so subtly and inexorably that I’d barely noticed. It should have been a terrible, shocking revelation — I guess it would have been, if I’d been able to care. Instead I finished my cigarette and didn’t think about it again, because as long as I didn’t let it fall into my line of sight it didn’t seem real, and as long as it wasn’t real I didn’t have to deal with it.

I want to say people who loved me asked me to get help, or that I had some kind of breakthrough that I couldn’t spend the rest of my life that way, but that’s not what happened. What actually happened is that I played Bioshock Infinite.

Bioshock Infinite is not a good game. It’s full of inexcusable racism, lackluster combat, and big ideas it doesn’t have the courage to do justice to. You play as a white man with brown hair who saves a girl who has powers she uses solely to help you, and you solve the rest of your problems by indiscriminately shooting people. There is no explaining away so much of what it is, and at this point enough ink has been spilled on its failures that they don’t need to be rehashed here. But for all the things it gets wrong — and it’s so, so many things — it gets so many things right about trauma.

The game features multiple lives and timelines as part of a treatise on quantum mechanics and lives unlived. If we narrow down protagonist Booker DeWitt’s story to one timeline, here’s what we get: we can be reasonably certain he did some pretty nasty things at the Battle of Wounded Knee, when, according to his birthday via a load screen, he was a few months shy of 17. It’s not entirely clear what he did, but it’s clear enough. He killed a lot of people, seemingly unnecessarily, for which he was lauded, as his war buddy Slate tells us: “We called him the White Injun of Wounded Knee, for all the grisly trophies he claimed.” It’s suggested in a few places that Booker has Sioux ancestry: according to bounty hunter Preston E. Downs, Booker speaks Sioux, and according to Comstock, “In front of all the men, the sergeant looked at me and said, ‘Your family tree shelters a teepee or two, doesn’t it, son?’” This ancestry, something to be ashamed of according to the racial and political tensions of the game’s time period, are perhaps what inspired his actions. The game doesn’t spend much time on this, however, shuffling us along to the death of Booker’s wife and his subsequent selling of his daughter Anna in response to accumulated debt, ostensibly the narrative’s inciting incident.

Trauma psychologist Peter Levine (as far as I know no relation to Ken Levine, Bioshock’s creator) looked to how animals react to violent threats in creating his PTSD treatment modality, which he calls somatic experiencing. According to Levine, animals will often go into a state of “tonic immobility”, or play dead, when faced with overwhelming experiences, the way a mouse goes still in the jaws of a cat. This serves several important survival functions: in addition to releasing brain chemicals that reduce pain, it can also cause the threat to lose interest; this is why people are advised to go limp when they’re attacked by wild animals. The disassociation, immobility, and numbing associated with traumatic experiences are a survival mechanism, and a useful one — as long as they end. In studies of people who successfully rebounded from difficult experiences, Levine found that the people best able to do this were those who had the opportunity to safely come out of their immobility after the event, whose nervous systems were given the space to complete these ingrained biological processes and understand the danger had passed. If a cat walks away from a mouse that plays dead, after a few seconds or minutes the mouse will spring to its feet, shake itself off, and run, no worse for wear. Trauma, Levine argues, begins when individuals don’t have a time, space, support, resources, or skills to follow through on this shaking it off. Their bodies never finish surviving an experience, and they get stuck in those moments, leading to the symptoms of PTSD. He writes,

Until the core physical experience of trauma — feeling scared stiff, frozen in fear or collapsing and going numb — unwinds and transforms, one remains stuck, a captive of one’s own entwined fear and helplessness. The… perception of seemingly unbearable experiences leads us to avoid and deny them, to tighten up against them and then split off from them. Resorting to these “defenses” is, however, like drinking salt water to quench extreme thirst.1

Booker’s split comes at a pivotal baptism scene, implied to take place directly after Wounded Knee although with no sign of the battle in sight. It’s here, the game tells us, that one version of Booker decides to become Comstock, washing himself clean of his sins, putting the past behind him, and eventually going on to create the floating white theocracy of Columbia. Yet Booker-as-Comstock is repression, stagnation, Peter Levine’s avoidance and denial; he deals with his trauma by powerfully and absolutely pretending it never happened.

That’s the salvific promise of the game’s understanding of baptismal doctrine; but the past, it goes on to show, cannot be wiped away. Columbia is Comstock’s monument to everything he won’t deal with, a testament to the all-saving power of staying stuck and the bandage on the unbindable wound of his actions. With Columbia he can write a new story about Wounded Knee, about the Boxer Rebellion, about the False Shepherd and the Lamb and the future and himself. With Columbia he can pretend that everything is fine.

I can’t blame him, because I did it too. I built my own Columbia every night I ended up surrounded by too many empty beer bottles, with every excuse I made when friends asked why they never saw me anymore. Nothing’s up, I’m just busy, you know how it is, everything’s great… It’s a tactic that works, in its way, but the ignored pain and guilt eat at Comstock; he even asks himself, “When a soul is born again, what happens to the one left behind in the baptismal water? Is he simply… gone? Or does he exist in some other world, alive, with sin intact?”

Infinite’s answer to Comstock’s question is that he does. Perhaps Comstock’s luring of Booker to Columbia with the strange promise to “wipe away the debt” is his way of setting in motion a work he’s let stagnate for so long he can’t budge it anymore. However, if Comstock keeps himself afloat through an impressively impossible ignorance, Booker dives headfirst into trauma with everything he’s got. The Booker who refuses the baptism leaves the Wounded Knee Massacre, which occurred in 1890; according to a load screen, two years later his wife dies in childbirth and he joins the Pinkertons, cracking skulls for anti-labor business owners. I’m not sure when in there he gives Anna to the Luteces, a mysterious, time-traveling brother and sister; some debt is paid, possibly gambling, but he doesn’t receive any money for it, and the debt seems to still exist when he heads to Columbia in pursuit of Elizabeth, a girl he’s asked to find and who we come to learn is actually his daughter. Having a wife and a family could have been the coming back to life Booker needed, but instead, when it ends in tragedy, he turned to the violent, ugly life of the Pinkertons. Peter Levine writes, “Humans… reterrorize themselves out of their (misplaced) fear of their own intense sensations and emotions… [making] the process of exiting immobility fearful and potentially violent.”2 Or, as Comstock tells Booker, “It always ends in blood.”

Unlike Comstock, Booker’s efforts are at least kinetic. He dives headfirst into the person he was, trying to solve his problems through the actions that caused them in the first place. Columbia was made for him by him, or another version of him. It is a playground for every one of his maladaptive coping strategies and a place where he can spin his wheels under the guise of getting better while simply rehashing the same old things. It ends in blood because he brings it, because he can’t bring anything else.

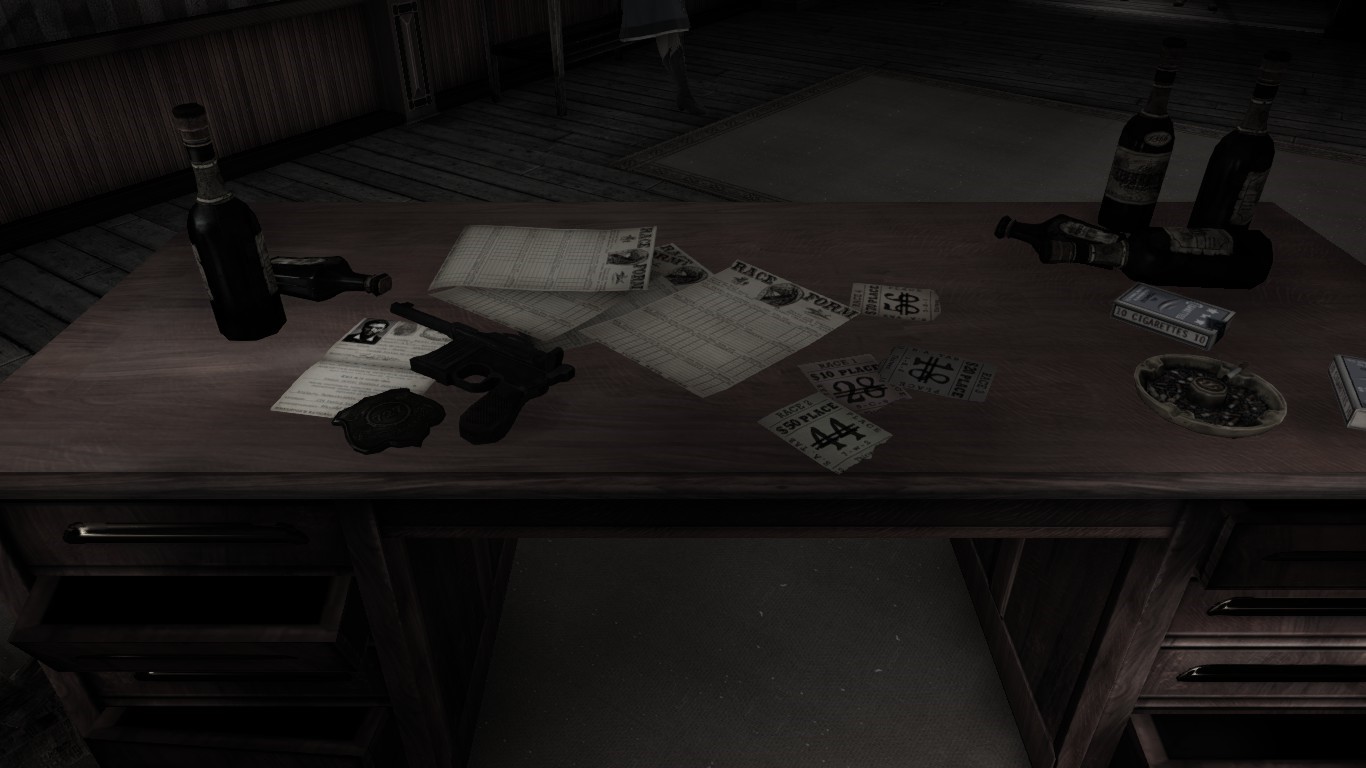

When I first saw Booker’s room in Infinite I gasped, because it looked just like mine — the same empty bottles and cigarette packs, the papers everywhere, the neglected bed, the color even, that same abysmal gray. We both seemed to work jobs we didn’t feel too good about. Looking at what we see of Booker’s life, I’d reason to say the two of us had been slowly starving ourselves of anything good for so long that when we first get a glimpse of Columbia, hear that emotionless “Hallelujah” as we clear the clouds, we trembled. The opening act of Infinite is ripe with life and colors, smiles and welcoming arms. As Booker, I played every fair game; I gorged myself on the food; I poked into every crevice and corner; I listened to every band and barker. I circled around and around the inevitable bloodshed, not knowing when it would be triggered but knowing it had to be — yes, because it’s games, but also because I knew we’d have to ruin it somehow.

When it does go wrong, Columbia is Booker’s ideal therapy room. In this floating city, everything that wrecks his life on the ground leads to success. Non-Columbia Booker clearly has a drinking problem, but in Columbia drinking makes him healthier. Non-Columbia Booker is pretty broke, if the losing gambling receipts in his room are any indication, but in Columbia people toss their riches in the trash; money is easy to come by and easy to spend. At the Good Time Club in Finkton, a powerful stranger offers Booker the job of head of security and forces him to “audition” for the role, according to the club’s marquee, through a series of increasingly difficult wave battles.

To me, this is Booker auditioning for the role of himself, a chance to indulge in all the violent impulses that lived in his heart through Wounded Knee and the Pinkertons and to be lauded and praised for them. His annoyance and his determination to just do the job that brought him to Columbia are all lies. There’s no way he isn’t enjoying it, because it all makes sense; it feeds back in on itself, re-traumatizing him, trapping him in that endless loop. He drags Elizabeth into it too, helping her deal with her dead mother through the same audition format: a series of wave battles with her ghost to prove herself worthy of the dead woman’s love. Early in the game the Luteces ask Booker to flip a coin, tallying heads and tails; Booker, annoyed, flips heads, and this is recorded on a list of 123 identical results. We learn later that Booker has played out this same story 123 times. It’s hard to say at what point it goes wrong, at what point it just starts all over again. As Rosalind Lutece says in one of her audio logs, “Why try to bring in a tide that will only go out again?”

Peter Levine writes that many trauma survivors feel shame about their trauma, and that “shame becomes deeply embedded as a pervasive sense of ‘badness’ permeating every part of their lives.”3 Neither Comstock nor Booker are good men. They’ve done terrible things, and they deal with their pasts by continuing to do terrible things, to other people and to themselves. For both of them, trauma and their responses become a feedback loop that gets harder and harder to break out of with each go around. Comstock’s dunk in the river and Booker’s seemingly straightforward mission are both the same, the lie we reach for in any struggle. Whether the problem is with our mental health or otherwise, we want someone to come along, something to happen, that will make everything better. That will stop us from making everything worse. But the best way out of trauma seems to be seeing those loops for yourself and stopping them, doing the hard work of finding a new path.

Infinite ultimately reveals that it doesn’t revolve around the baptism but around its characters’ choice to endlessly revisit what brought them to it in the first place. As the game’s complex ending unfolds through an endless ocean full of identical lighthouses, the entrance to Columbia, Elizabeth says to Booker, “There’s always a lighthouse. There’s always a man, there’s always a city…” Though on the surface a line about time, about the game’s recurring theme of constants and variables, this line is at the heart of Booker and Comstock’s trauma, the key to their repeating circles. It’s a line that drew me up short, because I heard it about me.

Because I knew exactly where that lighthouse was. It was the point I had been starting from, every day since all those things happened. In response to my trauma, I had broken my life up into chunks: there was before me, whoever he’d been before that winter, and there was after me, the man I woke up as every day since. I put what I saw as my badness on like clothes, I drank it like water, I left through that door in the morning and I came home through it at night. As I played through the end of Infinite and the game made its strange sense of Booker’s story, I understood what I had been doing to myself more clearly than any website or pastel-covered self-help book had been able to point out. I saw how I’d let my past define me, how I constantly ran it over in my mind, refusing to try a new door, a new way, refusing to let anything else in.

If people had done bad things to me I couldn’t make them stop by doing bad things to myself. Just as Booker couldn’t end the cycle of bloodshed with more bloodshed. Just as Comstock couldn’t end denial with more denial. Booker’s looping timeline showed me my own and pointed to the thing I seemed to most fear and yet most want: that I’d be dead inside forever, because even though it was terrible, at least I knew it was safe. When Booker decides to step away from that, to let his past drown him at the baptism, to submit fully to the weight of everything that happened… well. We don’t quite know if it breaks the cycle, but at least it’s something new.

I’d like to say I had some kind of breakthrough and was suddenly fixed, but trauma isn’t like that. A few weeks later I got myself into therapy, though. I did a bad job at it, honestly, and it didn’t really help. I was still — and still am — too scared to do the work required to make the trauma take up less space in my life. But I also got better, a little. I learned to be a little gentler to myself, to stop hurting myself when I was hurt. I leaned in, though carefully, to some of the things I was afraid of, and I started to feel for the edges of what could hold me up and what couldn’t, of what I could survive and what could breathe new life into me if I let it. I tried to learn to forgive myself for not being strong enough, and I tried to learn to honor the parts of me that had done their best to get me through. I just knew I didn’t want to be these men from this game, stuck in this endless, terrible cycle. I didn’t want to keep flipping that coin, drawing that number, answering that knock on the door. I still do, of course, and probably always still will, but it’s a little less every day. There are new lighthouses to make forays new, each a little different from the last, each a little better.

I just want to let you know I really liked this insightful piece. It’s cool that this game triggered some steps forward for you, all the best.

This is an incredible piece. Thank you.