This feature is part of our special series on History and Games.

Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation (and its remastered version Assassin’s Creed: Liberation HD)1 introduced new ideas to the well-known videogame series. In addition to the very first appearance of a female assassin as the game’s protagonist, Aveline de Grandpré, a disguise mechanic premiered which enabled the player to switch between her three different “social facades”, called personas.2 The master seminar “Pirates, Madams, Voodoo Queens: A Gender History of New Orleans” by Dr. Rebecca Brückmann that I attended at the University of Cologne inspired me to investigate the historical implications conveyed by Assassin’s Creed: Liberation’s vision of late 18th century New Orleans.

The game’s protagonist Aveline de Grandpré lives in the New Orleanian society of 1760, which is shaped by racial segregation and French rule. This contextualization of Aveline serves as foundation for a detailed analysis of the game’s disguise mechanic. This mechanic has a crucial role in the construction of the history the game portrays.3 Following the idea of a “(hi)story-play-space” introduced by Adam Chapman, gaming is understood as an active historical discourse between the player and the “developer-historian”. Only in an interaction between these two parties by the rules of the game – i.e. the game mechanics – can specific images of history emerge.4

Aveline is intended as an example of a free woman of color who grew up in a wealthy family. Her ambivalent social status is displayed in the different costumes offered by the game’s disguise mechanic. Every costume or persona directly translates to a change of her reputation and thereby conveys insights into the meaning of clothing for the constitution of social status. The practice of disguise in the depicted segregated society is interpreted as an act of liberation, as the game’s title suggests. Thus Aveline undermines the society’s dress regulations of her time to act free from societal and moral constraints and to be able to achieve her aims.

Treatment and legal status of slaves, manumitted slaves and free-born blacks was defined by the Code Noir of 1685 and 1724, a legislative text introduced during the French rule over New Orleans. This text played an important role in shaping 18th century New Orleans’ “three-caste system”5 which is crucial for an understanding of the historical potential of the game’s disguise mechanic. This “three-caste-system” creates a state of limbo for Aveline as a free woman of color between white rulers and black slaves which is the foundation of her fight for justice and freedom for New Orleans’ slaves. Her effort is carried by the first-time appearance of the disguise mechanic in the Assassin’s Creed series6 which includes the three personas: “Lady Persona”, “Slave Persona” and “Assassin Persona”.

- Lady Persona

- Slave Persona

“Lady Persona” and “Slave Persona” are two sides of one coin. The Lady Persona represents the upper end of the social “ladder”, the Slave Persona the lower end. Both represent a way of changing your social status through disguise and, by utilizing historical material, create options for action through the game mechanic. To generate historical imagery from this mechanic the player has to actively use it and be confronted with the possibilities and restrictions of the different disguises. These possibilities and restrictions directly transfer from the experiences Aveline makes in her respective persona.

By following its strictly ornamental purpose the “Lady Persona” (ill. 1) is a means to represent wealth and status. Although it restrains Aveline’s mobility with its numerous layers of clothing, its broad hat, and its tight corset, this costume allows Aveline to emulate the status of the white ruling class in New Orleans and to profit from their privileges. The notoriety level, for example, which determines how eager the city’s guards are to find Aveline and which increases when Aveline attacks someone or enters a restricted area, rises more slowly than in any other disguise. Climbing up houses or sprinting over rooftops, on the other hand, is far from what this costume was made to do, and therefore becomes impossible.

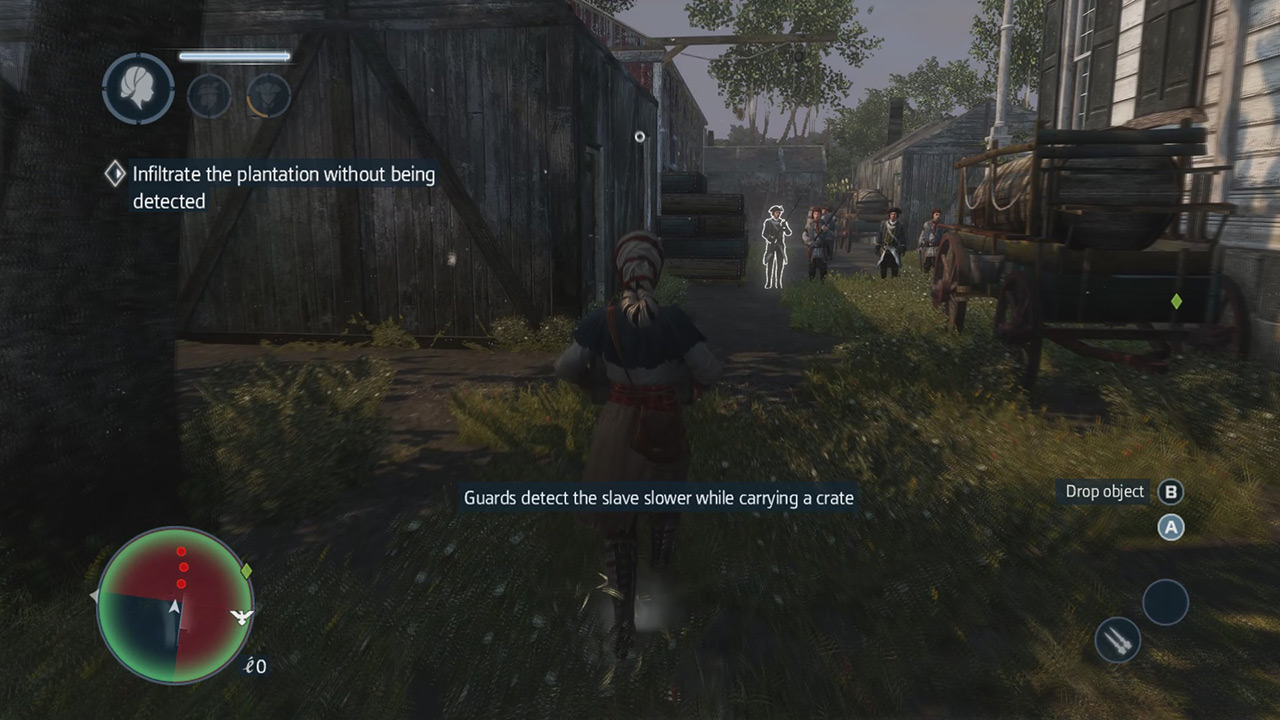

The “Slave Persona” (ill. 2), too, draws from contemporary conditions to create specific options for action. Disguised as a slave Aveline is able to hide in groups of other slaves to avoid detection by guards or to enter formerly inaccessible areas by carrying a box of goods (ill. 3). On the level of game mechanics bribing a guard in the “Lady Persona” (ill. 4) closely resembles deceiving the guards in the “Slave Persona”. What distinguishes both mechanics is that they embody different historical implications which only become transparent to the player if he uses said mechanics. Aveline exploits the excesses of inequality for her own ends while players gain access to new options for action in this historical framework. But while new options arise with every switch between “Lady Persona” and “Slave Persona”, others disappear. Any of the two disguises comes with a set of new restraints for Aveline in terms of her social status as well as for the player in terms of gameplay. Neither Aveline nor the player can thereby ever break free from the restrictions of the New Orleanian society of the late 18th century.

- Aveline using Chain Kill

- Assassin Persona

But there is a third costume: The fictional “Assassin Persona” (ill. 5) completes Avelines escape from society’s restraints. While using the circumstances to her advantage in the other two personas she only eludes the social restraints in her “Assassin Persona”. This persona stands in opposition to the reality of 18th century New Orleans and thereby symbolizes the coming alive of change and liberation in the person of Aveline.7 In this costume Aveline is an anomaly in time, which underlines the special role of the “Assassin Persona” in the triad of personas. Abandoning each and any façade Aveline becomes the city’s most wanted person and is attacked on sight. While the notoriety level can be reduced back to zero in the “Slave Persona” and the “Lady Persona” Aveline is always wanted when wearing the Assassin disguise. This new danger is the price paid for a liberation not only of Aveline but also of the player in terms of his options of action. The Assassin disguise gives the player access to Aveline’s full arsenal of weapons and gadgets; climbing and jumping pose no challenge for Aveline. Only in this costume the “Chain Kill ability” (ill. 6) can be used which enables the unleashed Aveline and the player to effortlessly eliminate large quantities of enemies.

Therefore, a liberation from societal restraints (from the perspective of Aveline) and from the restraints imposed by the game mechanics (from the perspective of the player) becomes apparent in the “Assassin Persona” as a deliberate fictional addition to the historical setting. The freedom of the Assassin Aveline is transferred to the player as a feeling of freedom experienced through the disguise mechanic. The act of disguising alone marks an escape from the conventions of different classes in the New Orleanian society. While being historically implausible in her actions, the fictional character of Aveline de Grandpré enables the player to switch between historical perspectives and come to an understanding of the society through the sharp contrast of the different personas.

It is apparent that historical imagery is not only generated by narration or historical reconstruction but also by the options of action offered by the game mechanics. Coming back to Chapman it can be concluded that a “reading” of history in games is accompanied by a “doing” of history which takes place in a (hi)story-play-space through which players travel and in which they create images of history by performing actions framed by the game logic.8

After approaching Assassin’s Creed: Liberation as a (hi)story-play-space and identifying the game’s disguise mechanic as a “doing” of history I wondered about how and why Aveline de Grandpré came to be. When asked about the influence of the history/historiography of the 18th century New Orleanian society on the creation of Aveline, one of the producers of Assassin’s Creed: Liberation at Ubisoft Sofia, Martin Capel, stated: “[W]e actually feel that we didn’t invent her, she was there just waiting to be discovered.”9 So it wasn’t by chance that Aveline took over from her male predecessors in this itineration of the Assassin’s Creed series. Quite the contrary: “In Liberation, Aveline is more than just an Assassin living in New Orleans – she is an integral part of the living city that she grew up in.”10 It becomes clear that the game’s developers consciously made a statement about 18th century New Orleans and the class of free women of color in their game. They succeeded in making this statement about the ambivalent situation of free women of color by choosing an uncommon approach, namely by merging historical material with the game mechanics through the disguise mechanic described in this article. By adding in the “Assassin Persona” the developers ultimately enable Aveline and, on a broader level, the free women of color to act independently. This emphasises an understanding of history in which formerly invisible social groups and their impact on society is focused upon. So while Assassin’s Creed: Liberation surely isn’t the most stunning release of the series in terms of its graphics or its narrative, it definitely is a forerunner in terms of the historical imagery it conveys and how it succeeds to do so.

While the implementation of a female protagonist and said disguise mechanic can also be seen as more of a marketing choice than an endeavor into the capacity of the medium to relive the past, it still raises the question how historical imagery is and can be conveyed in the Assassin’s Creed series and in videogames in general. I would argue that transferring historical material through game mechanics can achieve a higher degree of involvement of the player than transferring that material only through the narrative. Quite possibly both ways complement each other. But does some kind of involvement make one way better than the other? I’m not sure. Further research is needed to grasp the interconnection of narrative and ludological approaches to historical material in videogames.

Picture credits:

Assassin’s Creed: Liberation HD. 2014. Ubisoft Sofia/Ubisoft Milan. Playstation 3 (Playstation Network), Xbox 360 (Xbox Live Arcade), PC (Windows). Ubisoft. Chapter: Sequence 1.

All screenshots were taken by the author of this text.

- Assassin’s Creed: Liberation HD. 2014. Ubisoft Sofia/Ubisoft Milan. Playstation 3 (Playstation Network), Xbox 360 (Xbox Live Arcade), PC (Windows). Ubisoft. Chapter: Sequence 1. [↩]

- Following Merriam-Webster the term persona describes “an individual’s social facade or front that especially in the analytic psychology of C. G. Jung reflects the role in life the individual is playing” (http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/persona) [Accessed November 20th, 2016] [↩]

- Andrew B.R. Elliot and Matthew Wilhelm Kapell, „Introduction: To Build a Past That Will „Stand the Test of Time“ – Discovering Historical Facts, Assembling Historical Narratives“ In Playing with the Past. Digital Games and the Simulation of History, edited by Matthew Wilhelm Kapell and Andrew B. R. Elliott (New York, London: Bloomsbury, 2013), p. 17. [↩]

- Adam Chapman, Digital Games as History. How Videogames Represent the Past and Offer Access to Historical Practice (New York: Routledge, 2016), p. 51. [↩]

- Ira Berlin, Slaves Without Masters. The Free Negro in the Antebellum South (New York: Pantheon Books, 1974), p.198; Jennifer M. Spear, Race, Sex, and Social Order in Early New Orleans (Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2009), p.101. [↩]

- Previous iterations of the Assassin’s Creed series already offered ways to customise the protagonist’s clothing. The changes possible were, however, either of cosmetical nature (coloring of pieces of clothing) or solely had an impact on the game mechanics (e.g. improved protection from enemy’s attacks). The tightly interconnected narratological and ludologial disguise mechanic premiering in Liberation can surely be described as an innovation for the series. [↩]

- Jeanette C. Lauer and Robert H. Lauer, “Fashion” In The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Volume 4: Myth, Manners, and Memory, edited by Charles Reagan Wilson (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006), p. 61. [↩]

- Chapman, Digital Games as History, S. 51. [↩]

- “Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation producer Q&A”, Gematsu, http://gematsu.com/2012/08/assassins-creed-iii-liberation-producer-qa [Accessed December 20th, 2016] [↩]

- “Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation producer Q&A” [↩]