October and, uh, the beginning of November, is Horror Month here at the Ontological Geek! All of our pieces this month relate to horror in games, and we’ve got a bunch of great guest articles lined up for your enjoyment. We’re still accepting pitches for about a week or so, so e‑mail us at editor@ontologicalgeek.com if you have an idea!

Slender: The Arrival is one of those titles that snuck up on me. I’d first heard about it when it was just Slender: the Eight Pages; but after learning there was going to be a full game (written by the very excellent trio that write, film, and produce the Marble Hornets webseries) I resolved not to play the Eight Pages. Nor did I watch any of the many, many YouTube videos of people playing The Eight Pages, preferring to experience it all upon release. After all, Marble Hornets is a horror experience, and I certainly didn’t want to ruin The Arrival by knowing what happens ahead of time.

I then promptly forgot about it for the next several months, until the release of The Arrival.

There’s a method to watching horror movies: lights off, dark room, alone in the apartment. Violate too many of these and you guarantee a less interesting experience. So I satisfied as many as possible (it was still a bit light outside), and settled down. On boot, I got a screen reminding the player to allow themselves to become immersed in the experience (I tried to get a screenshot, but this screen never showed up on subsequent loads, even after uninstalling. It may have been removed in an update, unfortunately).

This was actually rather heartening; nothing ruins a good horror movie like picking it apart and refusing to become absorbed in it. Perhaps the authors knew what they were doing, and encouraging me to put myself in the best possible position to be scared was a good sign.

I was pleasantly surprised. Much of the atmosphere in Marble Hornets comes from its (except Entry #5) masterful use of sound: the staticky, staccato bursts of electronic noise and distortion that arise on film whenever Slenderman (or The Operator) is near. In fact, because that noise only appears when the film is played back, the viewer usually knows Slenderman is nearby long before the protagonists do, greatly increasing the tension as you watch. Along with that, visual tearing and distortion often make it harder for the viewer (or player, here) to see what’s happening, drawing your attention in before the bigger scares.

The second level of Arrival is a redesign of the original Eight Pages; the level that captured the hearts of so many beta players and YouTube viewers. It featured some well-placed lighting that left important areas in shadow, and a large enough area that I didn’t feel I really had a proper handle on where I was going. When Slenderman first appeared, I shouted and fled. I could feel my pulse quicken every time the static and distortion got worse, or when I suspected Slenderman was either behind me, or around the corner.

The second level of Arrival is a redesign of the original Eight Pages; the level that captured the hearts of so many beta players and YouTube viewers. It featured some well-placed lighting that left important areas in shadow, and a large enough area that I didn’t feel I really had a proper handle on where I was going. When Slenderman first appeared, I shouted and fled. I could feel my pulse quicken every time the static and distortion got worse, or when I suspected Slenderman was either behind me, or around the corner.

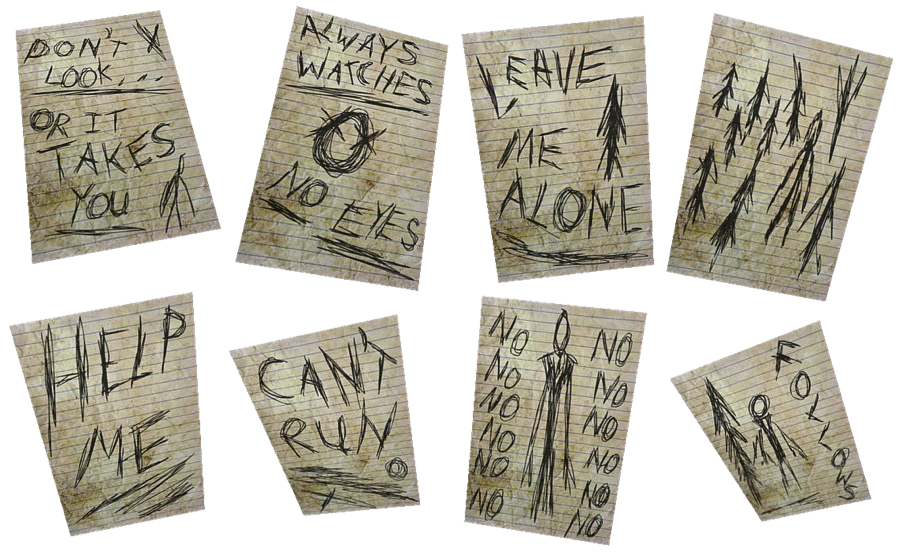

The goal of the level is to collect the Eight Pages, pieces of paper on which someone before you has scribbled sketches about Slenderman. They’re almost like doodles; simple enough you can take them in very quickly, but usually with some vaguely ominous message on them. Each of them is placed randomly around the level, though there are only 12 or so places they can appear. You have to collect each in order to finish the level, but if Slenderman catches you first, you’ll lose and have to start over.

The goal of the level is to collect the Eight Pages, pieces of paper on which someone before you has scribbled sketches about Slenderman. They’re almost like doodles; simple enough you can take them in very quickly, but usually with some vaguely ominous message on them. Each of them is placed randomly around the level, though there are only 12 or so places they can appear. You have to collect each in order to finish the level, but if Slenderman catches you first, you’ll lose and have to start over.

It was around the twenty minute mark, as I was missing one page and running in circles, that two things happened, and I stopped being scared.

First, I began to feel a growing feeling of frustration. If you’ve ever played a game that revolves around collectables, you know exactly what this frustration feels like (my first experience with it as a kid was Super Mario 64, searching for the 100th coin in the Lazy Maze Caves), and it’s never very much fun. As irritation began to overcome my fear, the charm of the visual distortions vanished. The static, rather than an ominous harbinger of nearby doom, became an annoying reminder than the last page might be right around this corner, but I didn’t have the time I needed to find it. Instead, I’d need to circle the area once more and come back. I ended up starting the level over, hoping that on a second try I’d be more successful.

Second, I started trying to game the system. I never felt like I had enough time to search through a particular building’s dead ends, since Slenderman seemed always on my heels, so I started trying to figure out a way to put a little more distance between us, hoping that I could find my last page. His AI seems to work about like this:

1.) Follow protagonist a little bit slower than her move speed

2.) Occasionally teleport randomly

It’s probably a bit more complicated than that, but this model worked well enough for me– I ran circles around the building until the static stopped, then assumed he’d teleported somewhere else and I’d have a moment to look. I was right, and on my second try I found all the pages without too much trouble. But after figuring out how he moved, knowing that if I turned around while he was still on my heels he’d just move towards me faster and the distortion would amp up, he stopped being a frightening character. Slenderman became merely another obstacle to be overcome.

This isn’t the only time I’ve seen frustration ruin horror either. Last year, my roommate finally played Silent Hill 2, after hearing me (and the internet at large) sing its praises. He came to me after failing the first fight against Pyramid Head several times, complaining that he never seemed to do any damage. What he didn’t realize is that fight is only overcome through surviving– Pyramid Head is invincible and you essentially just run away from him for a certain period of time before he leaves. After he knew, the fight became trivial, but the real damage was done; Pyramid Head no longer frightened him. He had become the object of annoyance, and so fear was no longer possible.

From a game design standpoint, this is troubling. Frustration is the key method by which challenge is created;1 too much frustration can be detrimental to the experience, but without it we might as well play FarmVille with unlimited real money to spend. But irritation leaves no room for fear: I cannot be both fearful and annoyed at the same time. How can a horror game become challenging and remain frightening at the same time? If I’d been led directly to that last page, there would have been no challenge and I wouldn’t have become annoyed, but if I ever realized the game was preventing me from failing, I wouldn’t be afraid either.

Truthfully, I don’t think there is an easy solution. There’s a fine line in horror for all mediums, but video games have a problem books and movies don’t: they must allow the player to fail. Without this, they become interactive puzzles to solve, they lose their teeth. This very failure, however, can ruin the possibility of fear: my personal failure meant I ran in circles searching for the last page, but my feelings would have been the same if I’d instead been caught by Slenderman twelve times and forced to restart. Additionally, what one player finds challenging, another may not. Dynamic difficulties that can adjust on the fly to their players’ skill level would be a start, but only careful, fine-grained adjustments that occur without the player’s notice have a chance of being successful. Only then, I believe, do we stand a chance of reaching for our teddy bears in front of our computer screens.

- Pulsipher, Lewis. “Much of Game design is Managing (and Causing) Frustration. http://pulsiphergamedesign.blogspot.com/2013/01/much-of-game-design-is-managing-and.html [↩]